Flashing fingers fly

And dance across the keyboard

Weaving their magic.

Feet too join the dance

Executing bass figures,

Sliding as on ice.

The word toccata

Means to touch—fingers, yes, and

Heart and soul and mind.

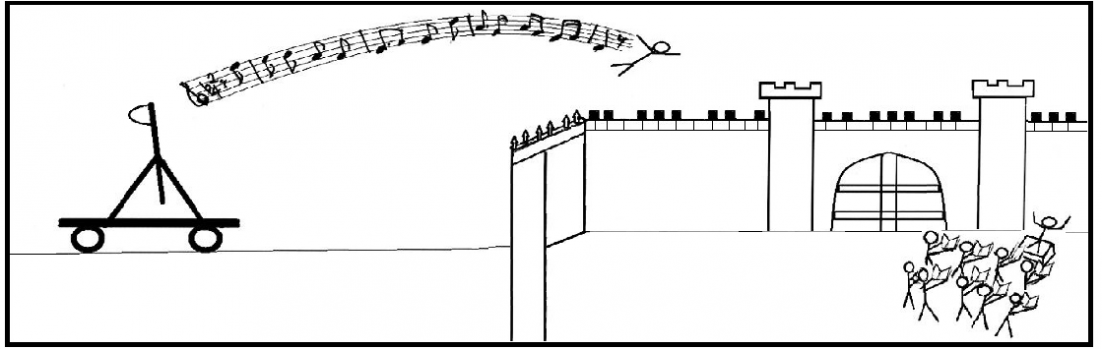

The toccata is by nature a flashy piece of music. It typically includes fast runs of notes, and can sound like an improvisation. It is a showcase for a musician’s skills. Toccatas are typically written for a keyboard instrument, but that’s not a requirement—toccatas have been written for string instruments, and even for orchestra (the prelude to Monteverdi’s opera L’Orfeo is a toccata). While the form had its heyday in the Baroque period, with Bach, master improviser, at the summit (Toccata in D Minor, the toccata everyone knows), the form never entirely went away.

Schumann wrote a Toccata in C (Op. 7) which he believed was the most difficult music at the time. In this video, you can follow the sheet music, which will give you an idea of the complexity. Liszt also gave it a whirl (Toccata, S. 197a).

Ravel included a toccata in his Le Tombeau de Couperin, and Debussy’s Jardins sous la pluie from Estampes is a toccata as well. One can also look to the finale of Widor’s Symphony No. 5 for a fine example of a toccata. You can find some videos of the finale here, including Widor himself playing the toccata.

Khachaturian wrote a toccata that became very popular (the suite it came from is nearly forgotten). The link features pianist Lev Oborin, who was the first to perform it.

For some real flash (and the piece that prompted this post) check out Prokofiev’s Toccata Op. 11. Here it is on a piano. Now add feet: here is the same toccata on an organ.

Benjamin Britten’s Piano Concerto begins with a toccata. The last movement of Ralph Vaughan Williams’s Symphony No. 8 contains a toccata. Also check out John Rutter’s Toccata in 7.

And now for the strings! The last movement of John Adams’s Violin Concerto contains a toccata, and Hindemith’s Kammermusik No. 5, a viola concerto, also contains a toccata (he also wrote a Toccata for a Mechanical Piano, meaning a player piano, which you can see here).

If you’re ever having a blah day, and need a quick pick-me-up, try a toccata!