Recently I had the great pleasure of singing Bach’s Magnificat in a fantastic choir with marvelous soloists and musicians. It was a thrilling performance, the music ringing in the hall, simply glorious.

Each time I sing one of the great choral masterpieces with them, it’s like adding another sparkling jewel to a treasure chest—the Brahms German Requiem, Handel’s Messiah, Mozart’s Vespers. Each one has its own unique beauty, and I learn something new from each one of them. Readers are already aware of some of the things I learned in preparing Magnificat (see here and here). But there’s something else that made this performance special, a first.

I sang it from memory.

But the memorizing itself is unimportant compared to what I learned from the performance.

It is amazing the things you notice when you can manage to pry the score loose from the death-grip with which your hands cling to it, fearful of missing a note or an entrance (or, worse, committing an unintentional solo), and raise your head for a prolonged period.

First, you notice the attentive, expectant faces of the audience. This would be terrifying if it weren’t for the fact that most of them are smiling. This only strengthens your commitment to sing your best for them.

Next, the choir director, whom you should be looking at most of the time anyway (but probably don’t—see death-grip above). But instead of the glance up from the score to check in for tempo, dynamics, a cue or special instruction (usually notated in my score by “WATCH!”), you get to see when they’re not looking at you (instead of vice versa). And you realize, as they cue every entry for every voice, that you’re not the only one who has things memorized, and in fact, they’ve memorized much more than you have. Which is just one of the reasons why they’re standing on a podium, and you’re not.

Another thing you notice, something you may take for granted, is the voices surrounding you. I don’t mean the person standing next to you, against whom you might cautiously check your pitch and volume. I heard the lines of entire sections, the earth-rumbling basses stating the fugue theme, the sopranos and altos singing the wonderful descending lines of the Gloria, fluttering downward like a twirling, falling leaf. The tenors adding their color notes and flourishes, voices arching dramatically skyward. And the sound is bigger, because you’re not hearing individual raindrops anymore—you’re hearing a torrent of notes.

And the instrumental music, by turns sweet, jingling, thundering, soul-stirring, each interweaving line issuing forth from the hands of a masterful musician, without whom the voices would seem incomplete. Fingers, flying, execute a precise figure, partnered in this instance with fleet-footed organ pedaling. A dance indeed.

You recognize the staggering number of hours that have been devoted by everyone to make this music come to life.

And finally, Bach. You realize he’s taken the word “dispersit” (scatters) and depicted it in the music, as it is repeated first to your left, then your right, directly in front of you, in back—surround sound hundreds of years before it existed. That beautiful phrase you recognize from the St. Matthew Passion? He used it here first, but you didn’t notice it before. And again and again he weaves magic into the music, and you are left awestruck by his genius.

I hope you will take time today to look up, and listen, and perhaps catch something you’ve been missing.

Me? I have a new score to memorize.

_____

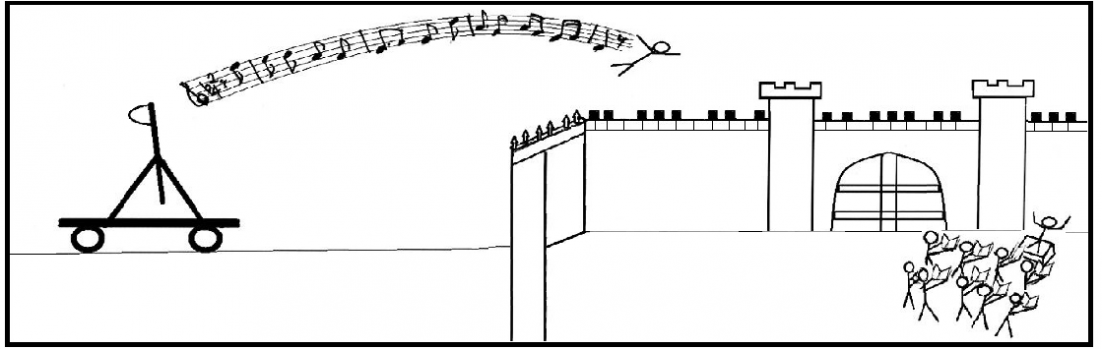

Image attribution: Musical catapulting stick figure. Copyright Chris Gallant 2015.