I have a piano. Actually, I have the piano. The one uniquely suited to my personality and temperament.

My piano does 11.

For those who don’t know the reference, in the movie This is Spinal Tap one of the guitarists in the rock band boasts that his amplifier is better than those of other bands because it goes to 11, not the standard 10. So it’s one louder (here’s the scene).

My piano is like that. It’s not a subtle beast.

It is not the finest piano I have played. My piano teacher has a Steinway that is capable of great delicacy, whisper-soft and silken, and rich full vibrant tones. In the right hands, it can create a great variety of color.

However, a Steinway was not in my budget. Nor was a buttery-toned Yamaha grand piano that I briefly considered. Given its price and large footprint, it didn’t seem a viable option.

My piano is a Yamaha W102. Its nearest current equivalent is a Yamaha U5 or U5 BB. It is not black; it flaunts its natural walnut grain (hence the W). It has a full composer’s desk to hold music, not just a ledge. It is 52 inches tall, the tallest upright model, and its harp (the ironwork frame upon which the strings are stretched) is as large as the harp of a baby grand. The W uses wood that is thicker and heavier than is used in the U series. This results in enhanced resonance. The warm, rich tones of both the wood and the strings endeared it to me then and have ever since. Here’s the blog post of another person whose ear was grabbed by a Yamaha W (paragraph 7, in particular). They called it “mellow and warm with a powerful bass.” Exactly.

It is likely to have started its life in the home of a family in Japan. I was told that there is no market for secondhand pianos there, so they are containered up and shipped to the US. As fraught with peril as this journey may have been (salty air and extreme dampness are not a piano’s friend), it made its way here, unscathed, to join a roomful of other Yamaha Ws and Us, Kawais, and other makes. These pianos are sometimes called gray-market pianos. Here’s an article on the subject.

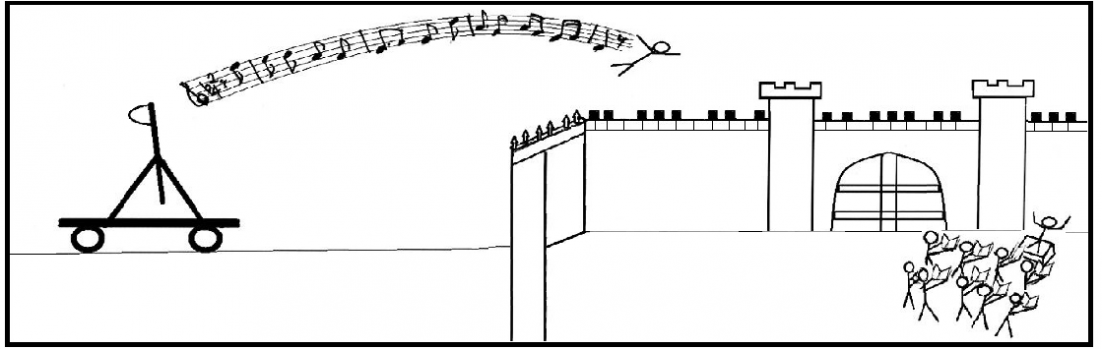

Its story on these shores began when my child needed a piano (the electronic keyboard I had at the time was insufficient). I made my way to the warehouse and started testing them out one by one. This was made slightly problematic by the fact that I didn’t know how to play a piano at the time, but such minor technicalities have never stopped me before. So I catapulted into the search.

I tested the sound of each piano and my husband checked under the hood for mechanical soundness. From the first chord, I knew this piano was special. We left to think it over, but an hour later I went back–I had to have that piano. I may have fallen in love, but I hadn’t lost my head: I left with a discount, a ten-year warranty, and t-shirts. And a beautiful piano.

There are times when I wish it (and I) were more subtle, but I wouldn’t trade that piano for the world.

And sometimes I vainly think Liszt would have liked my piano. He was the rock star of his time, and he regularly snapped strings during his energetic performances.

I think he could have used a piano that does 11.

_______

Image attribution: Photo of Yamaha W102 by C. Gallant, 2015.

![01100111 01110010 01100001 01101101 01101111 01110000 01101000 01101111 01101110 01100101 [Gramophone]](https://catapultingintoclassical.files.wordpress.com/2015/08/gramophone_1914.png?w=129&h=156)